|

How

to shoot yourself in the foot, or produce a "deer in the

headlights" response that will mess you up badly:

The way to produce paralysis is to ignore the check list below and try to begin

with the result (a perfect semester topic) without the journey--and

work--that's necessary to create a really good project that you

will enjoy doing, and will be justly proud of when you're done.

It's amazing how easy it is to fall into this

trap.

The best escape route is to follow the "road

map," which follows.

If you get

stuck, or are simply scared by the project,

please see your professor immediately. DON'T WAIT, because

you'll fall behind--and excuses after the fact are much less

credible than timely and sincere efforts to get the work done.

And remember that it's a rare faculty member

who will "bite" a student who sincerely wants to learn.

When dealing with faculty it's also wise to

remember the warning that "Grizz," a gifted restorer

of old homes here in the Hudson Valley, would give to potential

clients: "I only work with people who listen to me."

If you request and receive advice from your professor, make a

sincere effort to follow through on their suggestions before

returning to say that you're still having trouble. This is both

good manners and good strategy: if you show that you're serious

then your professor almost certainly will redouble his or her

efforts on your behalf. And almost certainly you will learn something.

If you DON'T follow through, it's only human

nature for your professor to devote most his or her limited time

and energy on students who are really making an effort. Don't

put yourself in a position of being written off as a poor investment!

Check List

for Week ONE -- following the first discussion in class of your

semester project. Be sure to follow ALL of the steps, rather

than just the ones that appeal to you.

1) Be sure you fully understand the assignment,

and ask for any clarification that

you need.

2) If you are assigned an open topic: Why did you decide to take the class? Right there

is a seed your project can grow from. If your professor gives

you a specific rather than an open topic, the steps

that follow will help you to address the assigned topic.

3) Browse through the required and recommended

texts for your art history class. Are

there any images--and text associated with the images--that you're

particularly drawn to? Read the sections that attract you, without

taking notes.

4) Using your reading in the text book(s)

as a springboard, do some surfing

on the Internet, keeping in mind that this is just to check out

what's "out there." It's NOT a search of Internet sources

to use for your paper, because so many Internet sources are unreliable.

Bookmark the most interesting websites so you can return, but

remember that often Internet sources are unreliable, and that

you will need to verify appealing / useful material in solid

sources. If you find a website that you think is immensely valuable,

Barnet includes a checklist for evaluating Internet sources on

page 289 of the 11th edition of A

Short Guide to Writing About Art.

But remember that a bibliography

that consists mostly of websites almost certainly will be weak

and inadequate.

5) Go to the Library and explore the stacks

to get a sense of available resources on campus. You'll be surprised

by what you find. The most efficient

way to do this is:

a) Start with a

search of the Library catalog to get a sense of the call number range

of the topics you may be interested in.

Why be concerned

about call numbers?? Marist

and most academic and research libraries use the Library of Congress

Classification. In this system, Library materials are

organized by category--and you can tell which category a book

belongs to by looking at the first letters of the call number.

For example, category N (and its variants NA, NB, etc.) includes

works relating specifically to the fine arts. But a savvy researcher

knows that there's much more "gold" in them thar stacks

("stacks" are the many rows of bookshelves in a library).

If, for example, you are researching Minoan art--the art of ancient

Crete--a Library catalog search will bring up books listed under

BL782, BL793, BL793, CB245, CD996, DF220, DF221, HQ1075, N5333,

N5635, N5660, NA267, ND2570, QE522, U29, and a digital book with

a call number starting with BL96. Why are these books scattered

all over the Library? Well, BL = religion / mythology. CB = history

of civilization. HQ = Family, marriage, women. QE = Geology.

And U = military science. Do you see how this broadens the researcher's

options--especially considering that in some ways art history

is a form of the history of ideas? Here are links to an article

that gives a good overview of the Library of Congress classification, and another

that explains how to read and use a call number.

b) Now that

you have some promising call numbers, go down to the stacks

to look for both specific books AND at the full collection of

books on the sheves either near your target book or in the call

number ranges you've identified--even the call number of the

e-book if it differs from the others you've found. If you take

your time, you'll discover books that you probably wouldn't find

if you just used the catalog. You'll also get a "hands-on"

sense of how works (for example) on architecture, painting, art

theory, culture, mythology / religion, history, and specific

periods of art will be in different parts of the library. All

you have to do is find a range of books that might interest you:

identify a call number category or a book that's helpful or interesting,

and then check the shelves close to where you found the useful

book.

c) Make a note

of the books that may be helpful to you--and if you're certain

you've "struck gold," borrow the book(s) from the Library

so you can do some reading at home. And please remember that

it's a kindness to your fellow students to return promptly the

books that end up being less useful as you'd thought.

Don't skip this step just because it's

a "nuisance" to walk to the Library.

This type of hand search is starting to be a lost skill, which

will set you ahead of the competition because it tends to result

in finding a wider range of material.

6) If you're not familiar with it already,

read some of the first chapters in Barnet's A Short Guide to Writing About

Art. Even if you ARE familiar

with Barnet, a quick review will probably help. If you felt you

can't afford Barnet (an expensive book) there are several copies

in the reference collection in the Library, and you can buy earlier

editions on Amazon.com for as little as a penny plus shipping.

Barnet will give you some ideas of how art historians often approach

their topics. Keep in mind that you DON'T have to choose one

of them. But this will give you some ideas as a springboard.

7) After a few days--within about a week

the first classroom discussion of the assignment--think about

your reading, library exploration, and surfing so far. Probably

some aspects of your chosen period of art are starting to become

intriguing, and some questions are starting to emerge. This is

the genesis of your project.

How will

you take notes?

It's now time to consider how you will

take notes for your paper. Especially

if your project is a large one, at this point it's important

to decide how you're going to

Organize your notes, so you can find things

easily, and

Choose or develop a system that works well

for you, so that you will know without question:

- The title and author

of the source you're drawing from

- The page number

that you found your information on

- Whether your information is a paraphrase

or a direct quote (an exact copy of

text written by another person). If your memory is very

good, it's wise to make a habit of quoting directly and indicating

clearly in your notes that this is what you've done. A person

with a treacherously good memory may paraphrase while taking

notes and then closely reproduce the original text in his / her

paper. If you're blessed with a memory of this sort, be sure

to finish your paper a few days before it's due. This way, you'll

be able to let it rest for a bit and then read it over and be

able to say to yourself, "Oops, I've read this before..."

and fix the problem.

|

You might consider using Microsoft OneNote,

which is a powerful searchable database for note taking--the

basic version is now available FREE, with versions for both PC and Mac. OneNote includes a good tutorial, is

available in most campus computer labs, and is part of the Microsoft

Office bundle, so you may already have it on your computer.

So long as you're careful to indicate in your

notes when you're using a direct quote, OneNote works splendidly

in conjunction with OCR (optical character recognition) software

such as OmniPage

that allows you to scan a source and then copy and paste text

into OneNote. If the cost is challenging to your budget, there's

no need to buy the latest version.

There are also free OCR software programs

available on the Internet (do a Google search for "free

OCR software") but be careful not to download unwanted software

or even malware at the same time. This is how sites offering

free software make their money: Unless you're very careful you'll

get an extra software piggybacking on the one you actually want.

|

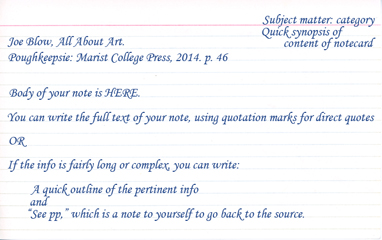

Click on the thumbnail above for large image |

| If you decide to stick

with physical notes, use 8.5 x 11

inch notecards instead of small ones. This will give you plenty

of room to include all of the info you need for each notecard.

It also will help to avoid writing on the back of the card--which

has the potential to drive you crazy as you look for something

on the fronts of a stack of index cards when it turns

out that you've written the crucial information on the back

of a card. |

Click on the thumbnail above for large image |

Writing notes in a notebook or using sticky

notes is OK for a small project, but

for a large project using a minimum of ten to fifteen sources

this quickly becomes unwieldy and will result in your wasting

time looking for your notes on a specific topic.

After the

first week: Finding your materials

8) Now it's time to read widely, THINK about

what you're reading, and start assembling a tentative bibliography.

As you read, your topic and how you will handle it will increasingly

come into focus. As your topic comes into focus it's time to

start taking notes, being sure to keep track of page numbers,

and what is a direct quote as opposed to a paraphrase. Again,

the strategies outlined below might seem cumbersome at first.

But remember that ultimately this method yields better results:

you'll have a wider range of information to draw from, and if

your aim is to gain a deep understanding of your topic, in the

long run it's faster.

Strategies to use:

1) Hold off for now

on our Library databases of journal articles.

2) Do a combination catalog and shelf

search

3) Approach books efficiently.

4) SNOWBALL!!

5) Use Amazon.com without conscience!

6) Consult bibliographies

7) Read

"Writing a Research Paper," in Barnet's Short Guide

to Writing About Art.

8) When

you're ready to do a focused search, use the databases

9) Assess your bibliography

1) Hold

off for now on our Library databases of journal articles. If you do a search too early

in your project you will get an overwhelming number of results

to sort through. The trick is to allow reliable authors do your

work for you: he or she will give you a good overview of your

chosen topic. Then, when your understanding is comprehensive

enough to be asking the right questions, you'll do a precise

database search (it's a good idea to ask a reference librarian

for help--they're great at designing searches) so that you get

a manageable number of results and find what you need quickly.

Do you see how this

saves time? Wrap your brain around an overview by competent scholars,

and then you won't need to sort through a huge number of journal

articles to understand the basic information in your chosen field.

A variant

of this strategy, which falls

under "snowballing" --and useful

when you're researching something that's entirely new to you--is

to find a good children's book on your topic that's aimed at

an 8-12 year old audience. Your initial response is probably

"WHAT??-- a children's book?!?" But you see,

children in the 8-12 age range adore facts, and it takes a competent

person to present the basic points of a topic in a clear and

engaging way that will satisfy this audience. If you read this

book, you'll get a quick and easy overview--and a good book of

this kind will have a bibliography for further reading. So, get

the basic overview, then you'll have the understanding to make

use of the more "grown-up" books. Tho this is a legitimate

technique, remember to leave the children's book out of your

bibliography, and to refer to your bibliography as a "Select

(or Selected) bibliography," which indicates that you're

listing the most important of the sources you used.

2) Do a combination catalog and shelf search--which

to an extent may overlap the search you did when following the

Checklist for Week One.

a) Now that you

have a clear(er) sense of your project, once again search the

Library

catalog to get a sense of additional specific books, and

by extension also additional call number ranges that may be useful to you. If you're not really clear

on how this works, go back and review the discussion

of call numbers in the Checklist for Week One

b) Armed

with your list of books to find and call number ranges to check

out, once again go down to the stacks to find specific books,

to search the shelves near these books, and also to search the

shelves in your chosen call number ranges.

This time, however, you'll be treating the

books differently: you'll be doing a careful evaluation of the

books you find, and will begin to "snowball"--techniques

that are outlined in the next two sections.

3)

Approach books efficiently. Before reading a promising-looking

book:

- Find the name of the publisher. A book by a major or small but reputable publisher,

or one published by a university press is probably pretty reliable.

- Check the back of the title page to find

the date of publication. A book written

in 1975, for example, may have much value, but it will be out

of date in some things.

- Figure that the information in most books

will be current about 10 years before the date of publication--for

more recent books this time will be less.

For example, a book published in 1975 will probably be current

for information that was cutting edge in 1965. Reason: It takes

time to write and publish a book. This is where recent journal

articles can be very helpful: as your project solidifies, you

can use a focused database search with a limited date range to

check out the most recent info on various topics.

- Read the table of contents. Some books have detailed tables of contents that

will help you decide to reject the book or lead you to examine

it more carefully.

- If the table of contents is promising,

read / skim the index in the back of the book. Sometimes a book will have just a few pages with

info you need. So long as you're careful not to pull information

out of context there's often no need to read a book cover to

cover.

- Check out the bibliography (more on that soon). If the bibliography looks solid,

this is promising. If there's no bibliography, you may want to

reject the book, as a scholarly book will tend have a bibliography.

When in doubt, go back and consider the publisher of the book,

the target audience, and also the reputation of the author. You

might also want to read some reviews of the book. If there's

no bibliography, but the book is written by a reputable scholar,

has a major or reputable publisher, but directed to a popular

audience, then using it will probably be fine.

- If everything looks good, THEN it's time to read the book.

- Remember that you don't need to read every

book cover to cover. Sometimes one

chapter is all you need, or just a few pages.

c) SNOWBALL!! Snowballing

is an old-fashioned and very efficient strategy to build your

bibliography and to find the info you need. (Imagine what life

was like when there were no computer databases to look things

up on, and a researcher would have to go through hard copy indexes--it

literally could take months!) The term "Snowballing"

is a metaphor: think of how children make a snow-man by rolling

a small snowball so that it increases in size by picking up more

snow.

To snowball:

Choose a source that you find very helpful,

then use this source as a springboard or signpost for where to

go next:

- Make use of an author's footnotes: if he / she mentions something of interest to you

and provides a footnote, look up that source, and snowball from

there.

- Check out the bibliography. Is there anything there that sounds promising? Look

it up, and continue snowballing!

- Does the author mention a topic that relates

to your interests? Look it up then

continue snowballing!

- Although typically an encyclopedia article

or Internet source is NOT considered an appropriate source for

a serious paper, you can certainly use these resources for

snowballing. For example, you can look something up in Wikipedia, which normally is not an acceptable

source to use in a footnote or bibliography, or Oxford Art Online (Requires Marist logon:

our library has a subscription. Check out the Library's Art and Art History page for links

to this an other resources). Read the article. Useful? Then check

out the bibliography of the article.

Do you see how snowballing lets other writers

do much of your work for you? They've already found good material

on your topic, and all you need to do is follow up on what they've

done. Of course a limitation of snowballing is that the sources

your chosen author uses are ones published before the

date of the source you have found so helpful. So, be aware of

the dates of the works you snowball from and be sure to check

more recent sources as well.

d) Use Amazon.com in conjunction with SEAL and WorldCat

Amazon is a VERY useful tool--especially when used in conjunction

with our Library

and InterLibrary Loan.

Our Marist Library catalog, Southeastern Access to Libraries (SEAL),

and WorldCat (World Cat requires Marist login)

are exceedingly helpful in finding Library resources on campus,

in the Marist area (SEAL), and worldwide (WorldCat). But these

catalogs don't have the same flexibility and power for identifying

things you may want. Amazon, of course, wants to sell you things--so

Amazon has a very high motivation (and budget) to help you find

what you need!

To use Amazon strategically:

- Go to the book

section of Amazon.com and type in any search term

that comes to mind--something you usually can't do successfully

with less flexible Library databases. Be inventive, and phrase

your searches in different ways. You'll get all kinds of results:

some obvious junk, and some gems. For many of the gems you can

use Amazon's "Look Inside" feature to check out the

table of contents, the index and some the first pages. Remember

that Amazon will mostly feature fairly recent books.

- Find something

promising?

Look it up in our Marist Library catalog and in databases for

other libraries: Southeastern

Access to Libraries (SEAL), and WorldCat (WorldCat requires a Marist logon).

Since Marist is part of the Southeastern Access to Libraries,

it will save time to search in SEAL first: You'll see immediately

whether Marist has the resource you want--and if it's not in

our Marist Library collection, you've already done the search

that pinpoints where the resource is.

- If we don't have

the book you want on campus,

request it IMMEDIATELY through Marist's InterLibrary Loan. It will help

to speed things along if you make a note of where the book you

want is and to put the location of the book in the appropriate

field of Marist's online InterLibrary loan form--being sure also

to mention where you found the listing (SEAL or WorldCat). SUNY

New Paltz, Vassar, and Bard are near Marist, do if one of these

libraries has the book you want--and it's listed as available--be

sure to note this in the appropriate spot on the online InterLibrary

Loan form.

- It's important

to move quickly--within the first few weeks of semester--to make

your InterLibrary Loan requests.

Typically it takes a week or two, sometimes three, for the book

to arrive. Usually you can take the book home, but be prepared

to photocopy as the loan period is limited--and sometimes the

lending library requests a restriction of Marist library use

only.

- The resources mentioned in this section

also appear as links on the Research

page of the Art History Resources

website.

e) Consult

bibliographies, which will point you toward "standard"

works in the field you're researching. And skimming through a

good bibliography will also give you a sense of who are reputable

publishers--so you'll be better able to evaluate books you encounter

outside of the context of a bibliography.

- Gardner's Art Through the

Ages, our History of Western Art 1 and 2 textbook, has in

its last pages a splendid bibliography that's organized by chapter

/ period. You may be confident that any work listed in this bibliography

is a solid source. Especially if you're an art major, note that

this book is long-term resource that's well worth getting in

hard copy: E-book subscriptions expire rather quickly. If you

don't have your own copy, check the Library--especially books

put on reserve by art history faculty.

- Most art history textbooks have a bibliography in their final pages, and--once again--you may be

confident that the works listed are solid. Be sure to check this

as well.

- Use the annotated bibliographies in our

Library collection, being sure to

check more than one so that you'll cover a wide date range. And

note that the Marmor bibliography is a continuation of the Arntzen

/ Rainwater one. Inevitably these will not list the most recent

books, but you'll be able to find the recent ones easily.

Eresmann, Donald L. Fine arts : a bibliographic guide to basic reference

works, histories, and handbooks, 2nd edition, 1979

Arntzen, Etta and Robert Rainwater. Guide to the Literature of Art History 1 (1980)

Marmor, Max. Guide to the Literature of Art History 2.

Chicago: American Library Association, ca. 2005. Covers works

published from around 1985.

f) Read "Writing a Research Paper," in

Barnet's Short Guide to Writing

About Art. In the 11th edition this is Chapter 13. In the section

of Chapter 13 titled "Finding the Material" (pp. 275-289)

Barnet gives a very helpful outline of the major art-related

reference materials and databases to consult. Our Library has

many of them.

Especially if you are an art history major,

be sure to get this book and become familiar with it as it will

help you immensely.

Barnet's book is undeniably expensive, but

an earlier edition will work nicely for you and is often available

on Amazon for as little as a penny plus shipping.

g) When you're ready

to do a focused search, use the databases. If you've followed

the earlier steps of this reasearch strategy road map, you should

have a fairly good idea of some questions you've not yet found

the answers to, gaps in your data--or things that you need to

verify in the most recent scholarship.

Now is the time to do a search--or series

of searches--that is focused and will get you exactly the information

you need.

Ask one of our highly skilled reference librarians

to help you to design a search of the databases listed on our

Library's Art and Art History page. You'll find that the

results of a clearly focused search will usually identify a fairly

small group of journal articles--so you won't have to wade through

a huge amount of literature to find the information you need.

h) Assess your bibliography to be sure that it's balanced

and has a wide enough range of sources. And remember that an

experienced reader will look at your bibliography before

reading your paper--just as you yourself did when assessing books

for their possible value to your project.

Here is a list of things

to consider when assessing your bibliography:

- Number of sources.

Your professor

will guide you on the required length of your bibliography, but

as a rule of thumb figure that for a carefully researched 15-20

page paper at least about 10-15 sources will be appropriate.

Remember that these are sources you actually use in your paper.

- Range of materials.

Be sure that you've searched broadly enough. For example, if

you're working with some aspect of Minoan art, your bibliography

would be too narrow if you listed 10 works, all of which had

some variation of "The Art of Crete" as their titles.

Depending on your paper topic, you might want to broaden your

bibliography by adding a works on (for example) symbolism, religion

/ mythology, architecture, biography, methods of making works

of art, methods of archaeology, and also one or more sources

on the culture of the period you're exploring.

- Dates.

Be aware of when your sources were published, and balance good

older sources with more recent ones to be sure that your information

isn't out of date. Remember that the information in most books

will be "current" about 10 years before the date of

publication--for more recent books this time will be less. For

example, a book published in 1975 will probably be "current"

for information that was cutting edge in 1965. Reason: It takes

time to write and publish a book. This is where recent journal

articles can be very helpful: as your project solidifies, you

can use a focused database search with

a limited date range to check out the most recent info on various

topics.

- In general, you

should AVOID encyclopedia articles in select (or selected) bibliography

of your completed paper [See below

for definition of "select bibliography."] Encyclopedia articles are

fine to consult for an overview, and to use for "snowballing." However, including in the

bibliography of your completed paper articles (for example) from

the Encyclopedia Britannica or Oxford Art Online

is a red flag that you've been lazy in your research. There are

exceptions to this rule, for example, the very useful Dictionary of the History of Ideas, which

contains articles by leading experts in their fields.

- Internet sources. Be sure that you evaluate Internet carefully

for reliability. Some are excellent; many are unreliable. Altho

it's fine to use even an unreliable resource for "snowballing," a bibliography consisting

almost entirely of websites will probably not be an adequate

one. Barnet presents valuable criteria to use when evaluating

a website on page 289 of the 11th edition of A Short Guide

to Writing About Art.

- One or more original

works of art may be on in your bibliography. If you choose an original

work of art, it is especially appropriate to use one that you

will be able to study in person.

- Textbooks are normally

NOT considered appropriate as a major source in your bibliography.

Unless you

are using a textbook to double-check information you'd like to

treat as "common knowledge," inclusion of your course

textbook in the bibliography screams out that you haven't really

done your homework.

- As your Select

(or Selected) Bibliography gets longer, you may find it helpful

to divide it into sections.

At the beginning of your bibliography put a short introductory

paragraph that says that you've organized your bibliography under

the following headings: a) ... b) ... c) ... and so forth. The

ellipses [...] indicate the place you'll put the titles of your

choice

- "Selected"

or "Select" bibliography. When assembling the final draft of your

bibliography there's no need to cite everything you looked at

in developing your project. Be sure to include everything that

you include in footnotes in your final draft. But there's no

need to mention sources that you used only for "snowballing."

This is where using the terms "selected" or "select"

along with "Bibliography" is very useful, as it indicates

that you are citing the most significant works that you consulted.

The Proposal:

Definition and reasons for assigning. To an extent, the word "proposal"

is misleading, as it suggests that you are outlining what you

plan to do in the FUTURE. To an extent a proposal does

indicate what your final project will look like, but remember

that a good proposal indicates that you've already done a third

to a half of the work needed to complete your project.

So, please take this

assignment seriously.

Two major reasons your

professor will assign a proposal are:

- To ensure that by

the due date you have assembled a tentative bibliography, done

a substantial amount of reading and have made crucial decisions

about the topic, scope, and structure of your paper; and

- To identify and discuss

with you anything that is of concern about your semester project

or term paper. It's much better to identify and correct problems

early on rather than ending up with a weak paper and much lower

grade than you would like.

It follows that:

- If you run into

a problem before the proposal is due, it's wise to meet with your professor

to resolve it. He or she almost certainly will be very happy

to help you.

- It's a really bad

idea to slack off in the early part of the semester and dash off a "proposal"

a day or so before it's due. If your hasty preparation is obvious,

then you'll have to re-do your proposal and meet with your professor

or receive written feedback when he or she is available--which

means you might have to accept a delay. And if your proposal

sounds plausible, you may have committed to something you can't

deliver on.

In contrast, a carefully researched and

written proposal ensures that you'll

have fairly smooth sailing for the balance of the semester.

The

long form of a proposal is

for graduate level work, and is at least a semester-long project

in itself. But it's worth looking at the description of the long

form of the proposal, as it will give you some things to keep

in mind both for the future and for ways you can improve a smaller

scale paper.

For example, an uncomfortable

question that undergraduate students rarely ask themselves is

about the need for the study: Why is my topic important--other

than to get a good grade this semester? Why would anyone

want to read it? Doing your best to address this issue will strengthen

your paper.

The short form of a proposal is

appropriate for most term papers, and consists of four parts.

a) A "problem statement"

/ statement of topic, which should be at most three sentences.

This isn't easy: to do it well you'll need to have a good grasp

of your topic and how you intend to handle it. One way to think

of your problem statement is as an "executive summary"

of your paper or project. Imagine you are at a party and meet

a person who might either offer you a job or an internship, who

wants to get a sense of your research skills and how your mind

works. He or she asks you about your paper. How would you describe

your project in a minute or less--before someone interrupts and

your opportunity is lost?

b) Statement of the reason

for your choice of topic. In at most 2 sentences, explain

how your chosen topic relates to your interests. Why did you

choose the topic? How does your topic relate to your professional

goals, interests you already have, or interests that have grown

with the independent reading you're doing? This statement very

loosely corresponds to the "need for the study" in

a formal (long form / graduate level) proposal. In the INFORMAL,

small-scale short form of a proposal, a carefully considered

statement of the reason you chose your topic will help to provide

focus. A clear understanding of why you chose your topic will

affect the way you approach your topic and organize your paper.

c) Outline. In simple

outline form, or in one paragraph, explain how you plan to approach

your topic. Based on the reading and thinking you've already

done, and on the bibliography you've assembled, what is the tentative

structure of your paper? This is not intended to be "written

in stone," for the project / paper will grow as you work

on it. HOWEVER, be sure that your outline rests on the strong

foundation of the work you've done so far.

In writing your

outline, consider whether you're writing a report or an

essay..

A report

is a well-organized summary of information the writer has gathered

on a given topic. In contrast, an essay is a sustained

argument in which the writer assembles evidence to support a

conclusion that goes beyond the sources he or she draws on. To

give a very simple example: "given a, b, and c, it seems

that the situation may be described as x." The writer of

the essay might find points a, b, and c in the literature, but

x is an original idea arising from careful consideration of the

available data. An essay, then, is a more advanced and sophisticated

form of writing than a report.

d) The annotated Bibliography

is the final part of a short proposal. By the time you write

your proposal you should have already assembled a solid bibliography.

Look again at the section titled "Assess

your Bibliography" and be sure that your bibliography

is balanced, and has a wide enough range of appropriate sources.

When

you are certain you have a solid bibliography, you may want to

organize it in sections. If you choose to do this, under the

heading "Selected Bibliography" say something like

"I have organized this bibliography under the following

headings: a) . . . b) . . . c) . . . " And then use the

headings, listing your sources alphabetically by author's last

name.

- List

your sources in the University of Chicago style (format),

noting that the format for a bibliographic entry differs in format

from a footnote;

- Add

an annotation for each entry:

- Why

will the source you've listed be useful to you? This might or

might not be obvious. And,

- How

are you going to access the source? Is it at Marist? Is it online?

Will you buy it or get it through InterLibrary Loan?

Documentation is crucial to scholarly writing,

and answers the savvy reader's very reasonable question: "This

is an interesting idea or statement. How does the writer--and

by extension, the I (the reader)--know that it's either true

or a legitimate theory or hypothesis?"

One way, of course,

is you (the writer) to write an essay, which

is a carefully developed argument leading to an original conclusion.

But if you are writing

a report (a carefully organized synopsis

of information you've gathered on a given topic) or for the component

parts of your argument (essay) you need

to show that your information (or data) is solid. You do this

by assembling a good bibliography and then pinpointing where

your specific facts or statements come from--with a citation

that includes both the primary or secondary source AND the page

number. Of course, if you're doing an original study and discussing

data you yourself generated, you would refer to your own work.

Below are discussions

of:

Finding

good images and documenting them

University

of Chicago Style, which

is standard for art history, and

The thorny question of how to identify "Common

Knowledge," and when it's OK to omit a footnote

Finding good digital

images and documenting them. There are a number of good reasons to use images in

your term paper--especially to make it clear to your reader what

you're talking about. You should plan on inserting the images

into the text of your paper in a way that will be the most helpful

to your reader. Then, of course, you must say where the images

came from.

- Finding good images is increasingly simple.

A good place to start is the image

source page of this website.

- There is no universally accepted format

for documenting images. Choose a format, and use it

consistently throughout your paper. For example, you could put

your source within the caption of an image, or you could put

it in a footnote or end note.

- Check with your

professor to confirm, but it will probably be fine to use the

names of well-known image sources, such as those listed in the image source page of this website.

The links lead either to the log-in page (ArtStor) or directly

to the "collections" pages where you may search for

and download images for personal and scholarly use. Remember

that for any use other than the "fair use" of images, such as using them

in an unpublished term paper or in a classroom presentation (NOT

posted a publicly accessible website) you will need to check

the Terms of use for each site.

For less well-known

online sources--ones you might encounter through a Google image

search--include the URL and the date you accessed the image.

- For images scanned from a book, Check with your professor to confirm, but it will

probably be fine to use full documentation, as you would in a

footnote.

- Sources of digital images. The image source page of this website contains

links to some major sources of good digital images.

- Bibliography: In your Bibliography, include

a section called "Image Sources," and present a simple

list of your sources, with URLs for the main page (or main "collections"

page) of such sites as ArtStor, etc. Include citations for books

from which you scanned images.

- If your paper is

accepted for publication,

you'll need a detailed acknowledgement of sources, and also will

need to arrange for licensing and the payment of any fees. So

be sure to keep a careful record of your image sources. Even

though image documentation may read: "Image source: Metropolitan

Museum of Art," it's wise to keep a note of the specific

URL of the image on the Metropolitan Museum's website, as this

will save time later. You'll find this task much easier if

you follow one of these methods: a) put a thumbnail image

and a URL and link in a section of your records on Microsoft

OneNote, or b) If you are familiar with PhotoShop, put this

information in the File Info field of each image. (Choose File

on the navigation bar near the top of the PhotoShop screen, and

then in the drop down menu choose File Info, and proceed from

there.)

University of Chicago

Style.

The University of

Chicago style is one of the two standard ones for art history, and the one that we use at

Marist for documentation (format of footnotes, etc.) of art history

research papers. It is particularly well-suited to the scholarship

of art history because the numbered footnotes allow for full

citations and also plenty of room for additional notes that in

your judgment don't belong in the main text of your paper. It

works best for your reader to put the footnotes at the bottom

of each page rather than at the end of your paper. And Microsoft

Word manages footnotes beautifully, re-numbering all them automatically

if you add or remove a footnote. Different editions of Microsoft

Word have different methods of inserting footnotes, so if you're

not sure how to insert a footnote use the "Help" function

in Microsoft Word or call our Help Desk (845 575-4357).

Unless you are citing

a web page or a source that was developed as a digital

resource, do your citation as if it were a hard copy source. For example, a digital version

of a book in our Marist Ebrary should be cited as if it were

a physical book, and a journal article that you find in digital

format through a database also should be cited as if it were

a hard copy source. It follows that there's no reason to use

the word "Print" at the end of a citation of a source

that you happened to consult in hard copy.

When using resources

in digital form, when possible consult the facsimile of the hard

copy so that

your page references will be correct. There are a number of electronic

databases that feature the same publications, and a traditional

citation is more informative than (for example) a Jstor URL.

Imagine a reader who wants to snowball from your work, but has

no access to the database you used, or may be trying to find

the source in hard copy.

Remember that footnotes

and bibliographies have different formats, and there are appropriate

formats for different types of publications. For example,

citations for a book and a journal article have different formats.

Listed below are some guides to the Chicago

Manual of Style:

Barnet's Short Guide to

Writing About Art includes a good overview of the basics of the University

of Chicago style. In the 11th edition the page numbers are 335-344.

Instructions for citing electronic materials are on pages

289-92.

The Chicago Manual of Style

Online gives an overview that is

brief and helpful for quick reference.

The Citation Machine allows you to fill out

an online form, and then generates a citation in the Chicago

Style:

Citation Machine NEW

bibliographic entry only

Citation

Machine OLD footnote

& bibliography

An extensive and detailed guide that you probably won't use right away is: Kate L.

Turabian's A Manual for Writers of Research Papers, Theses,

and Dissertations--which is constantly going into

new editions. So don't go out and buy this until you really need

it. We have a number of copies of Turabian in our Library's collection.

Here's a link to the newest edition available

in the Library.

"Common

knowledge." We all know that there's no need to footnote

information that's widely known, or "common knowledge."

But how do you know for sure when a bit of information is REALLY

common knowledge?

The rule of thumb

is that if you find the same fact in three reputable sources,

then it's fine to drop the footnote--being sure that at least one of those

sources is in your final bibliography.

This is fine, but it

doesn't take human nature into account. We humans have a way

of latching on to a source or viewpoint that makes sense to us,

and disregard other viewpoints as irrelevant. . . . that is,

until it gets to the point that we can no longer ignore the other

voices.

There's a method to

counteract this limitation in human nature, a method that at

first may seem absurdly laborious. But it's good craftsmanship,

will keep you out of trouble, and has the potential to improve

your credibility. As you become more experienced in your field,

you'll need it only when you move into new territory. But it's

a good idea to use it at first--and it's not hard if you have

organized your notes well.

The method

and rationale follow below.

The final step in writing

a paper is of course preparing the final version of your paper.

You may want to skip ahead to this step and then backtrack when

you've finished reading the section on the rationale.

Method: "colored footnotes." Here's what to do:

Here's what to do:

1) Write your paper

as you normally would, being careful to document (footnote)

all of your facts carefully--including the page number of your

source. You will, of course, NOT use footnotes when the ideas

are your own--for example, when stating the results of your own

careful analysis of theory, facts, or a work of art relating

to your topic. Put these first footnotes in BLACK text.

2) When you're done,

look critically at your documentation. Which footnotes strike

you as documenting "common knowledge"--the sort of

thing that a person familiar with your topic would know? These

footnotes that you've identified are candidates for being placed

in the "common knowledge" category, and--ultimately,

but not right away--omitted from the final version of your paper.

3) Double-check

these facts that you judge to be candidates for the category

of common knowledge, looking for two other solid sources

that say the same thing. At this point, it's OK to use a textbook

or a reference work, such as Oxford Art Online.

a) When find a second

source that says the same thing, ADD another citation within

the same footnote (that documents a given fact). Only this

time, put the citation in a DIFFERENT color, such as blue.

b) Do this again, looking

for a third solid source that documents the same fact. Add a

third citation, this

time in another color, such as red. Here's an excerpt from the paper by

a student who did this very well: EXAMPLE

of colored footnotes correctly done (Microsoft Word format)

c) You may find that

there's some difference of opinion in the sources you're using

for common knowledge. This is a GOOD finding! See below (Rationale) for an explanation.

Remember that this

is something you do ONLY for facts that you judge are probably

common knowledge.

Leave the remaining footnotes alone.

4) You'll now have

a rather colorful draft of your paper. Some of your footnotes

will include triple citations--the first in black, the

second in blue, and the third in red. Be sure to end this draft

of your paper with a bibliography that includes the sources you

used to nail down facts that are common knowledge. In this bibliography

you may want to identify sources you used for common knowledge

only by changing the color of the text of their bibliographic

entries, perhaps putting these entries in red text. Now your common knowledge sources will

be easy for you to spot--which is important as you will consider

removing some of these works from the bibliography of the final

draft of your paper.

Rationale: Why bother

with colored footnotes?

Colored footnotes

help to correct for your own human error, and (as far as possible) to eliminate

embarrassing mistakes from your paper.

- When you find and

use use a source that's really helpful, it's only human nature

to slide into assuming that what the author says is correct,

and that other views may be safely ignored. By double checking

your facts, you are pushing yourself to be objective, AND strengthening

your paper. Remember that if a knowledgeable person reads

your paper and finds obvious factual errors, he or she will assume

that there are other errors that are not obvious--and will reject

your work as unreliable.

- You may find that

the fact you've identified as potentially "common knowledge"

is universally (or almost universally) acknowledged. Good finding. For now, leave

your colored footnotes in place.

- Or you may discover

that there are different views on the fact that you're double

checking. This

ALSO is a good finding, as you will then modify your paper to

reflect scholarly disagreement. You might simply say that the

issue is a topic of lively discussion--perhaps with a footnote

to give examples--OR you may find it wise to add a few sentences,

or even a paragraph, in the main text of your paper to outline

the main divergent views of the issue. Remember that the University of Chicago

style lends itself to putting YOUR observations in the footnote,

if you judge that a given observation is important to a serious

reader, but doesn't really belong in the body of your paper.

You will see examples of this in your reading.

- If you decide to

develop your topic in the future, having your complete documentation all

in one place will be very useful.

PLEASE KEEP IN MIND

that if your professor requires this method, taking a shortcut

by fabricating the footnotes is a very serious form of plagiarism

/ academic dishonesty, because it is evidence of

a delibrate effort to deceive. If discovered probably will earn

you a failing

grade for the

semester--and may raise the question of whether you belong at

Marist.

There's at least one

more step to take before preparing the final draft of your paper.

But you may want to skip ahead briefly and see

how you'll edit the completed colored footnote version of

your paper.

On Plagiarism:

Avoiding trouble

We all know that plagiarism is Not Good!

But there are times when it may be unintentional. Listed below are three forms of plagiarism. The first

is obvious; it's important to be aware of the other two, as they

may not seem as clear cut. As Marist's reputation continues to

rise and the value of a Marist degree becomes increasingly valuable,

concern about academic dishonesty continues to increase as well.

Faculty typically use turnitin.com

to screen for plagiarism, are required to report instances of

academic dishonesty. These records are kept in the files of the

Center

for Advising and Academic Services, and it follows that when

faculty uncover academic dishonesty the first thing they do is

call to find out if the student in question has been reported

before. If a student is on file as having been caught before,

then this is distressing for all concerned, and may be the first

step toward expulsion from the College.

So, if you're having trouble completing your

assignment, it's wise to go and talk to--NOT e-mail--your professor

and let them know what the situation is. You might be granted

an extension--but if you aren't it's much better to submit a

weak paper with perhaps too many correctly cited direct quotations

(with quotation marks, or a "block quote" and footnotes)

than to be caught in academic dishonesty.

Plagiarism includes:

1) Submitting all or part

of a paper written by someone else.

2) Copying sentences and

or phrases from a source (book, etc.) without putting this text

in quotation marks, and without supplying a footnote that identifies

the source.

The rule of thumb for deciding

whether a footnote is needed is: More than THREE consecutive words, not counting "a"

"the" or "and" need quotation marks and a

footnote.

Beware of the too-close

paraphrase.

Three consecutive words (excluding "the" and "and")

may be used without quotation marks or footnote, provided that

it isn't an unusually good phrase. For example, the phrase "Italian

Renaissance Art" is in common use, it's hard to figure out

how to say it another way without clumsy phrasing, and hence

it doesn't need quotation marks. In a contrasting example, the

cake baked by Kipling's Parsee, which was "indeed a superior

comestible" DOES need quotation marks, and / or some reference

to Kipling as the author: it's a distinctive--and in this case

famous and amusing--phrase.Whether a phrase of this sort needs

a footnote or just quotation marks and an acknowledgement of

the author is a judgment call. The bottom line is that you must

indicate that you borrowed the phrase.

Some students will quote three or four

words without quotation marks, put in a bridge of a few of their

own words, and then a short quoted phrase without quotation marks,

another bridge of their own words, and so forth. This also is a form of plagiarism--even tho any

of those quotations alone would be fine. Stringing quotations

together like beads on a string is considered plagiarism because

usually the student is editing a paragraph, and keeping the original

author's structure and many of his/her words. By doing this,

a student is suggesting that the organization of information

and a good bit of the text are the work of the student rather

than the original author.

3) False documentation:

Intentionally citing in a footnote or bibliography a source that

you did not in fact consult--or is not the source of a quotation--is

a form of plagiarism, / academic dishonesty and is considered

more serious than a paraphrase that's too close to the original

text that the writer has acknowledged as his or her source.

The reason it's considered

more serious is that it reveals a deliberate attempt to deceive

rather than the kind of inadvertent error that we all make from

time to time.

Examples of false documentation:

- Plagiarizing from a website,

but footnoting the plagiarized text to a scholarly book or article.

- Claiming to have examined

a work of art in person, but instead using images in a book or

museum website

-

- 5) The next step is to

SAVE the completed colored footnote version of your

paper with a new file name that indicates what it is. This

new file name could be: YourLastName_PaperTitle_ColoredFootnotes.docx.

Now that you have saved this version of your paper you will KEEP

this file to hand in by the due date.

6) The FINAL VERSION of your paper: Now

save the colored footnote version of your paper AGAIN with a

DIFFERENT name, which includes the word "FINAL." This new file name might be: YourLastName_PaperTitle_FINAL.docx.

When you finish the steps below this will be the final version

of your paper.

- Go through

your paper (in the FINAL version), and delete all footnotes that

include citations from three sources. This,

of course, is why putting the second and third citations in different

colors (such as blue for the second source, and red for the third) is so

useful. The colored footnotes are easy to see, so you won't delete

a footnote that should be there. Here is an EXAMPLE:

the same excerpt from the student paper that we looked at before,

with the colored (common knowledge) footnotes removed. See

how much shorter the paper becomes? It's also rock-solid, and

NOW the remaining footnotes will be helpful to an interested

reader.

- Prepare your final "Select Bibliography,"

OMITTING many of the sources you used to nail down the common

knowledge footnotes.

You will, of course, KEEP any source that:

- You also used as an important source for

the paper, or

- Appears in at least one footnote in the final

version of the paper,

-

-

|